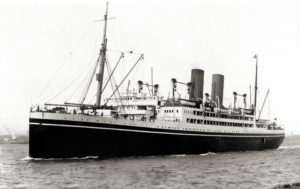

On July 23rd, 1920, a 10-year-old boy stood at the railing on deck of the S.S Minnedosa, watching the busy work happening at the Liverpool dockyards. Icek was tired and nervous, weary from the journey from Poland to England. His older brother Yankel, just 11 years old, was standing beside him, to his left. Their little brother Hymy was sitting on the wet deck, leaning against the back of Yankel’s legs, trying to stay awake. The boys had adjusted to travelling without their parents, of relying on the kindness of strangers and putting their faith in chance and circumstance.

“Thank God we made it this far,” Yankel might have said. Icek shook his head and rolled his eyes to sky. He was already questioning the existence of god, and was trying to imagine what life would be like once they got to Toronto. Who would be waiting for them when the ship landed in Quebec City? How would they get to Toronto? Icek and his brothers were sent away during the height of the Polish war with Russia, but not before he has witnessed the horrors of war; death, food shortages, displaced families and rampant anti-semitism.

“Thank God we made it this far,” Yankel might have said. Icek shook his head and rolled his eyes to sky. He was already questioning the existence of god, and was trying to imagine what life would be like once they got to Toronto. Who would be waiting for them when the ship landed in Quebec City? How would they get to Toronto? Icek and his brothers were sent away during the height of the Polish war with Russia, but not before he has witnessed the horrors of war; death, food shortages, displaced families and rampant anti-semitism.

The new world across the ocean held the promises of freedom and adventure. Icek knew almost nothing about Canada, other than its climate was not dissimilar to Poland, a number of family members were already there and working, and the vague references that life would be better there. Seven days after boarding the Canadian Pacific Shipping Line’s ocean liner, the Fruchtman boys landed in Quebec City, with rings of dirt around their necks, the growl of hunger in their bellies and the spark of dreams in their eyes.

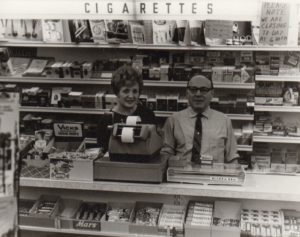

My grandparents were hard workers. My grandfather – who changed his name from the Polish version of Icek to the more anglicized Isaac – started his working life as a dressmaker and raincoat cutter. My grandmother – Sylvia – was a dutiful wife and mother, taking care of the home and spending her days with extended family, but she wanted more. When my grandparents opened up their goods store on the main floor of the apartment building they were living in, my grandmother was proud of how far they had come. Now, in the 1970s, it was perfectly acceptable for women to be working outside of the home, and it gave her something engaging to do now that her daughter was grown, married, and about to have a child of her own. My grandparents were equal partners in the business: the workload was shared and the pride of ownership was clear, even to me, whose earliest memory of that shop was me being allowed to pick one treat on Fridays before they closed for Sabbath.

“You own all this?” I asked, looking around with wonder at the shelves full of all manner of foods and household stuff. I had just walked into the shop, dwarfed by the rows of shelves in the middle of the space, the high shelves lining the walls and the displays of candy bars at the front counter. I was amazed that they had so much stuff, and more importantly, could let me pick whatever I wanted and not have to pay for it. This was a big deal to an 8-year-old.

Perched behind the cash register, my grandfather looked over at me and smiled. “Well, we still have to pay for everything, but we can keep the money from our sales.”What would you like to have today? Chocolate? Chips? Candy?”

I was overwhelmed by the choices and the options. “Can you come down here in the middle of the night and take whatever you want?” I asked, picturing my grandmother coming down the elevator in her nightgown, unlocking the door and grabbing a can of soup.

My grandfather was nodding and about to answer when the bell above the door rang and a customer walked up to the front counter to buy a pack of cigarettes. My grandmother appeared out of nowhere, got the cigarettes and rang up the sale.

“Do you need matches or a lighter?” she asked. “Lighters are a dime, matches are a penny.” She did not wait for the man to affirm whether he needed either. Her hand was already reaching for the matches.

“Sure, I’ll take some matches,” the customer answered.

That’s how the business was built. One penny pack of matches at a time.

I was amazed that my grandmother was able to sell something that a customer didn’t even ask for. She anticipated a need, and introduced two options at two very different price points. It’s like she knew that presenting the the lower cost matches at the end of her sentence would guarantee the sale. She was shrewd when it came to business, but she was smart enough to not let it show too much. Running a variety store (or tuck shop if you prefer) was hard work. The hours were always long, the margins were sometimes minimal. But this was their baby. If they wanted to move new pipes, they could put them front and centre. If they wanted to get rid of items that didn’t sell, they could mark them down. They could say yes and no as they pleased to salesmen offering new items. They relied on themselves for their paychecks. They got to know the names of their regular customers, all of whom came from the three buildings the store served. They didn’t call themselves entrepreneurs, they called themselves grocers.

My father’s side of the family also had deep roots in retail. My uncle – my father’s brother-in-law – opened a chain of furniture stores in and around Toronto, Ontario. A salesman to the core, my uncle orchestrated a publicity stunt that took him to Alaska in the 1960s to sell a refrigerator to an Eskimo. My father was a store manager at one of the many locations, eventually moving into a district manager role. My aunt was a business hobbyist who started business out of boredom. My father ran a couple of them for their very short business lives until he decided to venture out on his own. My father ran his CB radio business out of the basement of his house. He wore all the hats: acquisition, distribution, shipping, and accounting. He worked long after everyone had gone to bed. He spent days on the road, selling and delivering radios, 6-foot antennas, and anything that had to do with radios.

Unlike my grandparents, my father seemed exhausted most of the time. He enjoyed meeting with customers, making every call in person last longer than it needed to. I don’t think he had passion for what he was selling, he was merely eking out a living. He built great relationships, but made poor choices. He would drive 4 hours to deliver a $50 product. He would ship a single power cord overnight, paying more for the package than the value of its contents. Not the best business model.

With such a family history in retail, I guess you could say that I was born with sales in my blood. But that doesn’t mean I was any good at it. Yes, I could probably sell a swimsuit to a mermaid, but I wouldn’t feel good about it. My conscience drives me, and that is something that is not welcomed or encouraged in retail. Rather than sell the swimsuit, I would send the mermaid to the best place I know of where she can get reliable tail maintenance. I want to be helpful more than I want a commission. I value relationships with customers over sales figures. I watched my grandparents thrive, my uncle become a multi-millionaire and my father toil for a few bucks in the bank. I subconsciously learned all I needed to know about running a business – a retail business specifically – just from watching my family. Still, when I landed my first retail job at the age of 15, I was sorely unprepared, stupid and made a horrible mistake.